This essay it is best served with music.

There is a place called City N. It exists and it does not exist. It is real and it is fictional. It is anywhere and it is nowhere and it is somewhere. The annals say no date when the first stone was laid in City N nor the names of the majors nor dates of matters, both joyful and sad. Not that City N has nothing of that – no, it does – but nothing particular you would emphasise. It is concrete and it is abstract. It is, what I would like to call it, an antiplace[1].

It is also called “a county town N” or “a provincial town N” or “City NN” or “city N” or “Ensk” and appeared widely in Russian literature in various guises. Gogol wrote about it in The Government Inspector and Dead Souls. Chekhov featured it in his stories, as well as did Dostoevsky, Turgenev and others. Perhaps, it was even overused, but it was rather a zest than a cliché. Thus starts one of the greatest first sentences you may ever witness:

There were so many hairdressing establishments and funeral homes in the regional centre of city N that the inhabitants seemed to be born merely in order to have a shave, get their hair cut, freshen up their heads with végétale[2] and then die. – The Twelve Chairs, Ilf and Petrov.

City N is a toponym that writers used to depict an archetypical provincial, remote city or town or district – a geographical object where the story was set. The literary critic Stepan Shevyrev wrote about City N as a standalone character in Dead Souls:

…living ... its own full, whole life and created by the poet's comic imagination, which in this creation has played out to its fullest and has almost disconnected itself from real life.

It wasn’t just one of the provincial cities of the Russian Empire, it was a collective image, spotted by the author in different corners of the country and merged into a new, strange whole. City N often had a set of archetypical characters playing the same roles, which Shevyrev defined as:

The official part of City N was represented as a governor, a tulle embroiderer, a prosecutor, serious and silent, the postmaster, a witty philosopher, the officiary, a judicious, kind and good-natured man, a policeman, a father and benefactor, and other officials, divided into fat and thin[3]. The unofficial part consists of firstly, enlightened people who read Moskovskie vedomosti[4], Karamzin, etc., then of tyuryuks, baybaks[5] and ladies who call their husbands by the affectionate names "kubyshka"[6], "fattie", "bellyman", "chernushka", "kiki" and "zhuzhu". Of those ladies, two have particularly distinguished themselves: the lady who is simply pleasant and the lady who is pleasant in every way. The city's temperament is the kindest, hospitable and most simple-hearted, its conversations are stamped with some special brevity, everything is family-oriented, everyone is fraternal and so between each other. Does the city play cards or not, it has his own particular sayings and expressions for every suit and every card. Whether they talk among themselves, they have their own proverb for every name, which doesn't offend anyone.

Often City N acquires ironic and satirical connotations endowed with specific features. It is a city where morals are savage, or at least, traditional, the nature of events – absurd, or at least anecdotal, hence, the awareness of the inferiority and pointlessness of life – strong, and time – whatsoever flawless and motionless. Think of it as a “nexus” city, a place connecting together many other places, taking the most representative aspects of each, binding archetypes together. At the same time, it can be used to connote a place that doesn’t need to be named. Just like often a character needs no name, a place where a story happens does not require any specification at all. It either can happen anywhere or it doesn’t matter where it happens because the focus is on characters or story events. Using “City N” is not the same as not naming a place of action at all. Indicating to the reader that the story unfolds in City N means that it happens somewhere, and there’s likely your personal “where”, but where this “where” is exactly, who cares? It is a minimalistic approach to worldbuilding. The writer builds only characters and shows what happens to them and the world then grows from that naturally or just proverbially exists around them as a set of reusable theatre decorations.

Anton Chekhov used it exactly that way. Although City N as a toponym was used by many of his colleagues, the universal, uniting meaning it holds only in Chekhov’s stories. He did not always call it City N, and often did not specify the place at all. Sometimes it was ‘Town B, consisting of two or three curvy streets’ (Pharmacist, 1886), ‘A little provincial town N’ (The First Debut, 1886), City / Town or Posad K / N or any other letter. The name is not as important as the concept of repeating a poetic image. Chekhov used a special set of descriptions for places, which gives us a feeling as if all of his stories happen in the same universe with the same boundaries (Chekhoverse, lol, please pardon my Degen-esque). He amplifies these boundaries over time, adding new links to the chain, making its poetics evolve and enrich itself. Everything that happens in Chekhov’s short stories and plays, happens in some Russian city, its dachas nearby, churches and villages, beyond which is nothing – uninhabited wilderness, which Chekhov called “on the road”, “on the way to the city” as if there was nothing else, only City N.

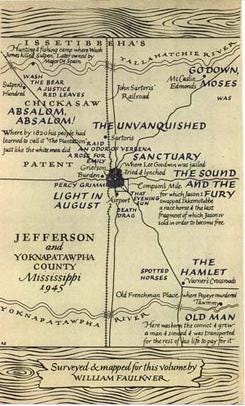

By creating a spatial artistic image that encompasses in its orbit many plots and genre variations and all kinds of accidents, fates and faces, Chekhov not only continued the narrative tradition but acted as a forerunner and founder of its new version. The concept of City N was used before him and after him, even outside of Russian literature. Take William Faulkner as an example. Fifteen of his novels and many of his short stories are about the people of the small county of Yoknapatawpha located in the American South, in Mississippi. He referred to it as ‘my apocryphal county’ and even drew its map. Later, Jesmyn Ward, inspired by Faulkner, also used the county in her work.

There are, perhaps, many other such cases of lands fictional but heavily inspired by real places (the author is planning to write about at least one more soon), but they, and Yoknapatawpha county, are often aware of its explicitly fictional nature. At least, it has both the map and the territory (kind of) and a concrete imaginary name. City N is different because it’s anonymous and abstract. You don’t know where it is – it’s not in the middle of Western Russia, not in Siberia nor in the Far East, neither you know what exactly inspired it. It is everywhere, nowhere, anywhere: somewhere, it’s an antiplace (yes!). When you see “City N”, the first thought is that the location is not important, cities are all alike, so who cares?

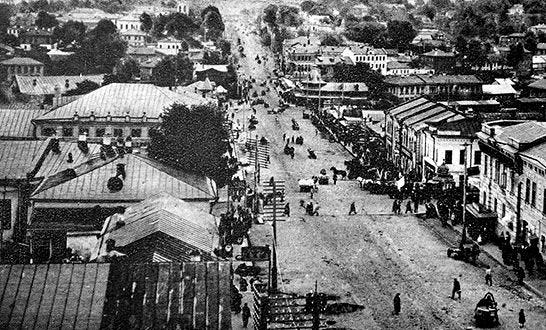

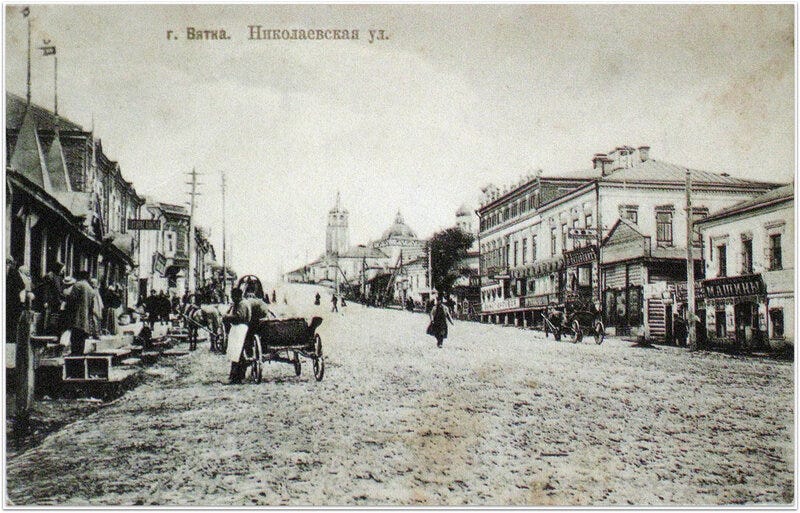

The question stands, if it’s a collective image, how fictional is City N and is it just an archetype? Chekhov, Faulkner and others were not building fantasy worlds. The main stage for their locations and characters was the real world. Chekhov was one of the authors who also travelled a lot and he was known for depicting the mundane situation and people as they were, often satirical, of course, but nevertheless true. But there was another great Russian writer, Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, who was “prosecuted for freethought” and “penally transported” to Vyatka (now Kirov), one of the popular places whither the government exiled people. Coincidentally, it is the biggest city – around 600 thousand people – in proximity to the village wherein I grew up, but also the city wherein I spent my six university years. For Saltykov-Shchedrin in the 1850s, that city was a perfect encapsulation of City N. He wrote:

There is a city in a distant corner of Russia that speaks to my heart in a special way. Not that it is distinguished by splendid buildings or their own Semiramis’s hanging gardens, and shan’t you find even a single three-storey house in a long row of streets, all unpaved; but there is something peaceful, patriarchal in all its physiognomy, something soothing to the soul in the silence that reigns on its hills. Entering this city, you feel as if here and now your career is over and you can no longer demand anything from life, you only have to live in the past and digest your memories. Indeed, there is nowhere else to go beyond this city, as if the world ends here.

And also:

One of the most striking peculiarity of our remote towns is that it is almost impossible to meet there people from somewhere else. Whoever you see in the streets, squares, public places, shops – all of them are local people who live here because they gradually acquired some kind of natural fetters. There is nothing for a stranger to do here and that is why there is no reason for him to come. It is true to such an extent that there is no provincial person who would not be aware of this truth and look with surprised eyes at the stranger who is dashing to escape. The provincial town has never served as a goal for anyone, but only as an obstacle, which you would’ve flown over only if you had wings.

. . . Which is the truest truth about the city even now, after 170 years since it was written. Everyone I know among those who have been Vyatka laughs or at least smiles melancholically and ironically after reading these two paragraphs above, admitting and acknowledging them, especially those many who “dashed to escape” and “had wings”, including myself.

After the Russian Empire ended, all of its copious City Ns entered the Soviet era which hyperbolised it even more, ideologically and practically, applying a trope as a methodology of developing the country. The whole vastness of it turned into one big City N – the same grey people working the same monotonous jobs in the same ugly buildings. Whenever you travel, you’ll find the same “white house”, a governmental building (which is also grey, by the way), a Lenin statue[7], or two, a school, a post office, a hospital – all looking and feeling the same, shops with the same goods at the same prices, people speaking one enforced standardised language with glimpses of dialects and accents if the language isn’t native. National and personal identities were washed out or at least were not encouraged, and everything became an archetype of itself. There was, and sometimes many people think there still is, only Moscow and “other cities”, a copious selection of Ensks feeding the maw. That’s why and how City N can exist and feel so natural and even obvious. You don’t even need a name for a city, after all, regardless of the year, if you grew up in one of such Ensks then everywhere you can feel at home. . .

- One day, I’ll elaborate but you can get the idea from this essay, I’m sure.

- A green, violet-scented liquid. Made from mild spirit tinted green and violet perfume, used as water for hair. It has no medicinal properties but cleanses the hair well.

- This is indeed a reference to one of the most known Chekhov’s short stories, Fat and Thin. The story shows two quite archetypical characters having a dialogue at the railway station.

- It was Russia's largest newspaper by circulation before it was overtaken by Saint Petersburg dailies in the mid-19th century.

- Layabouts, slackers

- Kubyshka is an early East Slavic ceramic jar or pot with a narrow hole, a short or absent neck and a wide, rounded body.

- There’s a theory that a legion of Lenin statues in post-Soviet countries serves as beacons and trojan horses for aliens, so when they arrive to ditch finally us for our human sins, the army of those terracotta warriors will come alive and take the murderous war on humanity, wreaking havoc and annihilating everyone and everything with their laser eyes (red, of course).